Sacred Currents: A Deeper Look

Explore Sacred Currents: Spirituality in African Art

The text within this educational webpage was written by Daniel Jones. Professional photos of objects in the exhibition (unless otherwise noted) were taken by Elizabeth Black and the exceptional student photography team at Polk State College.

A Deeper Look - Sacred Currents: Spirituality in African Art

Sacred Currents: Spirituality in African Art examines the myriad of ways in which material culture and practices across Africa and the African diaspora materialize spirituality. The works assembled in the exhibition, ranging from twin figures (venavi, hohovi, ibeji, togbovi) and Fon bochio protection objects to beadwork, masks, headdresses, and Haitian drapo (flags), exemplify the enduring capacity of African material culture to embody significant meaning.

Structured around the themes of Ceremony, Protection, and Grief and Memorialization, the exhibition examines these objects within the ritual and social contexts from which they are from. Headdresses, for example, operate as active instruments in ceremonial performance, mediating between spiritual and earthly realms. Protective works, such as bochio or ritual beadwork, exemplify the belief that material substances, when ritually charged, may intervene in the spiritual realm. Objects of grief and memorialization, including figures created to honor deceased twins or to preserve ancestral presence, embody the persistence of spiritual continuity even in the wake of loss.

This section of the Lake Wales Arts Council website extends the exhibition into a more scholarly space, offering critical analysis of themes, symbolism, and material practices. Through close attention to form, function, and meaning, you will uncover additional information on how these works are not merely aesthetic creations, but vital instruments of belief that sustain and transmit spiritual life across generations.

Ceremonial

Artifacts integral to rituals, rites of passage, celebrations, or communal gatherings.

The Mossi peoples of Burkina Faso are renowned for their dynamic sculptural traditions and the complex integration of spiritual power into their material culture. This baga (diviner) headdress, associated with a Mossi baga, exemplifies the convergence of material richness and beauty, ritual symbolism, and social function. The baga headdress shows craftmanship, aesthetic beauty, and commands respect and importance in its context. Cowrie shells, fiber tassels, and braided strands adorn the headdress projecting both visual splendor and spiritual potency. Baga headdresses are expertly made and are durable so they can be passed down to other ancestors or successors. Further increasing the headdress' spiritual prowess, it was handed down from previous generations.

The dense covering of cowrie shells serves as more than decorative embellishment. In West African spiritual and economic systems, cowrie shells historically functioned as a medium of exchange, but more significantly, they act as conduits of divinatory power and protective forces (Berns, 1989). Their gleaming white surfaces are also associated with purity, water, and fertility, showing the diversity in usage and meaning of cowrie shells (Drewal & Schildkrout, 2009). For diviners, the cowrie’s association with a myriad of significant spiritual symbolisms and material culture links the physical and spiritual realms, amplifying the authority and strength of the baga during divination ceremonies.

The elongated vertical crest and trailing tassels make the headdress into a more dynamic form which emphasizes movement and presence in performance contexts. The visual expression communicates and enhances a diviner’s ability to mediate between earthly and spiritual domains, channeling messages from ancestral spirits and deities (Roy, 1987). Art in Africa is general dynamic and kinetic, and the baga headdress is a great example. The movement of the headdress and regalia, along with the noises of the shells, the iron gongs, and other musical instruments, aids in communicating for divinatory practices and enhances the effectiveness. In Mossi tradition, baga occupy a vital position as interpreters of misfortune, illness, and conflict. Their regalia not only mark their social distinction, it also embodies the spiritual efficacy and fortitude required for their work. The baga headdress thus operates as both a material symbol of sacred authority and status, and an active participant in ritual performance.

Through its astonishing craftsmanship regarding aesthetics and geometric order, organic movement, and significant symbolism, the Mossi baga headdress highlights the profound interconnectedness of art, economy, social elements, and spirituality within Mossi life in Burkina Faso traditional people groups. Within the context of Sacred Currents: Spirituality in African Art, it testifies to the enduring power of material culture as a vessel of sacred knowledge, social continuity, and method of communication for the Mossi people.

References

Berns, M. C. (1989). The Art of Power/The Power of Art: Studies in Benin Iconography. Museum for African Art.

Drewal, H. J., & Schildkrout, E. (2009). Sacred Waters: Arts for Mami Wata and Other Divinities in Africa and the Diaspora. Indiana University Press.

Roy, C. D. (1987). Art of the Upper Volta Rivers. Alain & Françoise Chaffin.

Roy, C. D. Speaking With God: A Mossi Diviner

Mossi Baga Headdress

Burkina Faso

Late 19th–Early 20th Century

Cowrie shells, Leather, Fiber, Cloth

Collection of Daniel Jones

The isikoti (wedding cape), is a central garment in Zulu marital attire, worn by brides during the marriage ceremony. Isikoti such as this one demonstrate the sophisticated integration of beadwork, cloth, and symbolic design that define Zulu ceremonial dress. Isikoti are constructed from richly colored cotton panels, and the cotton panels are overlaid with intricate and sophisticated beaded embroidery, arranged in patterns that create a sense of layered depth, symbolism, and rhythm for ceremonies. The usage of geometric motifs, most notably diamonds, triangles, and chevrons, are not simply for decorative purposes but to carry coded messages of identity, lineage, and social standing within Zulu society (Jolles & Jolles, 2004).

The beaded looped pendant strands draping from the central oval emphasize the garment’s performative quality for marriage. When worn, these pendants would sway with the bride’s movement, animating the surface and transforming the cape into dynamic art. The visual richness and symbolism of the isikoti highlight its role in marking the solemnity and joy of marriage. The beadwork often communicates emotional states, relational bonds, and spiritual invocations, functioning as both personal adornment and as social features (Beck, 2000).

In Zulu cosmology, marriage ceremonies represent not only the union of two individuals but also the joining of two families and ancestral lines. The isikoti's elaborate craftsmanship situates the bride within the continuity of tradition while helping to create her new spiritual and social identity as a married woman. Zulu Isikoti highlights how dress functions simultaneously as art, interpretive text, and ritual object, embodying the deep interconnections between spirituality, aesthetics, and social life in Zulu culture.

References

Beck, R. B. (2000). African Ceremonies: The Rituals and Traditions of Africa. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Jolles, F., & Jolles, S. (2004). Zulu Ritual Art: Symbols, Customs, and History. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press.

Kloppers, P. (2017). Beadwork, Art and the Body in Africa. Pretoria: University of South Africa Press.

Zulu Isikoti

South Africa

Mid 20th Century

Fabric, Beads, Fiber

Collection of Daniel Jones

This finely beaded Yoruba apo Ifa (divination bag), served as an essential object within the practices of Ifa divination. Apo Ifa were used to hold the ikin Ifa (sacred palm nuts) and other implements employed by the babalawo (priest or diviner) in the complex process of communicating with Orunmila, the deity of wisdom, destiny, and divination. These sacred palm nuts are extremely significant in Yoruba culture and are believed to typically have eye-like patterns, which strengthen the divination process, helping to better see and analyze results. Beyond the practical role of the apo Ifa, the bag also functioned as a statement of ritual authority, status, and aesthetic refinement within Yoruba religious culture where beads are paramount to material culture and way of life.

The elaborate beadwork on the apo Ifa reflects Yoruba mastery of glass bead embroidery, a medium closely associated with royal and sacred arts. The central motif, framed by radiating geometric patterns, likely references cosmological themes: the balance between earthly and spiritual realms, the organizing power of Orunmila, and the priest’s mediating role between humans and the divine. The star-like and diamond patterns across the necklace are protective and metaphysical symbolism, while the colorful palette signifies vitality, sacred energy, and divine presence. The face on the apo Ifa is an effigy of Eshu, also known as the deity of the spiritual crossroads, a messenger and communicator, master of all languages, and is an integral part of the Yoruba cosmos.

The materials: leather backing, cotton lining, and brightly colored beads, illustrate the interconnectedness of Yoruba artistic production. Despite signs of wear, the bag retains much of its visual brilliance, attesting to its continued use and the reverence accorded to it. Within Yoruba traditional beliefs, the apo Ifa is more than a container: it is a vessel of sacred power, embodying the authority of the babalawo and the enduring wisdom of Orunmila. This apo Ifa highlights the ways in which material artistry, spiritual belief, and social identity converge in African religious traditions.

References

Abiodun, Rowland. Yoruba Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Drewal, Henry John, and Margaret Thompson Drewal. Gelede: Art and Female Power among the Yoruba. Indiana University Press, 1983.

Bascom, William. Ifa Divination: Communication Between Gods and Men in West Africa. Indiana University Press, 1991.

Yoruba Apo Ifa

Nigeria

Late 19th–early 20th century

Fabric, Leather, Beads

Collection of Daniel Jones

This finely beaded necklace, known as an odigba Ifa (necklace), is a ritual object used within the sophisticated Yoruba divination system of Ifa. The odigba Ifa serves both a symbolic and functional role within Ifa practice, embodying cosmological concepts while also marking the authority of the babalawo (priest or diviner).

The necklace is composed of multiple strands of glass beads in various arrangements and is interspersed with large spherical beads and culminates in two triangular pendants elaborately embroidered with geometric beadwork. Each pendant displays distinct motifs: one side with concentric spirals of blue beads suggesting cosmological wholeness, and the other with diamond-shaped patterns referencing balance, multiplicity, and the ordering of the supernatural realm. The color symbolism is significant within Yoruba aesthetics: white connotes purity and connection to the orisha Orunmila, red denotes vitality and power, while blue and yellow evoke spiritual depth and prosperity (Drewal and Drewal, 1983; Lawal, 2001).

As an emblem of Ifa, the odigba is not merely decorative but encodes sacred knowledge. The pendants are sometimes described as “faces” of the oracle, protecting and channeling the aṣẹ (vital force) of Orunmila, the deity of wisdom and divination. During consultations, the necklace may be worn by the diviner or placed upon the opon Ifa (divination tray) to sanctify the ritual process and affirm the babalawo’s spiritual authority (Bascom, 1969). Objects such as this demonstrate the Yoruba philosophy that art is inseparable from ritual and moral order. The shimmering surfaces of the beads are rather luxurious materials historically obtained through long distance trade that amplified the objects prominence.

References

Bascom, William. Ifa Divination: Communication Between Gods and Men in West Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1969.

Drewal, Henry J., and Margaret T. Drewal. Gelede: Art and Female Power among the Yoruba. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983.

Lawal, Babatunde. “Àṣẹ: Verbalizing and Visualizing Creative Power through Art.” Journal of Religion in Africa 32, no. 1 (2001): 32–60.

Yoruba Odigba Ifa

Nigeria

Early 20th Century

Beads, Fiber, Fabric

Collection of Daniel Jones

This headdress from the Dan peoples of Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia embodies the dynamic interplay between aesthetics, spirituality, and social identity in African art. Dan headdresses are integral to masquerade traditions, prominent to the Dan peoples, which serve not only as theatrical performances but also as vital vehicles of spiritual mediation, moral instruction, and communal regulation (Fischer & Himmelheber, 1984; Vandenhoute, 1948). This headdress combines organic and ordinary materials: cowrie shells, beads, animal hair, and dyed cloth, all arranged to create both visual richness and symbolic resonance. Cowrie shells are historically used as currency in West Africa, and they signify wealth and spiritual protection, while the red textile evokes vitality, power, and life force (Bargna, 2000). The addition of animal hair suggests to be amplifying the conduit between the physical and ancestral worlds, reinforcing the headdress’s role as a spiritual channel and commonly seen in African art.

Headdresses of this type were typically worn on the head and attached to wooden masks during initiation rituals and public ceremonies, where they enhanced the mask’s authority and transformed the masquerader into a liminal being who bridged human and supernatural realms (Fischer, 1963). You can see examples of headdresses like the one in Sacred Currents still attached to masks in a couple of photo examples above. The elaborate ornamentation on these headdresses elevates the mask’s presence, signaling its sacred potency and underscoring the importance of the performance in maintaining cosmic and social order. The vertical form of this headdress, capped with bead and cowrie embellishments, further emphasizes elevation and connection to the spiritual realm.

In the cosmology of the Dan peoples, masquerades embody spirits that guide and protect the community, ensuring things like fertility, justice, and social cohesion. (Fischer & Himmelheber, 1984). Although this headdress' exact ceremonial usage is not known, it is not merely decorative, but a material articulation of Dan spiritual thought and an object that transforms cloth, shells, and hair into a nexus of sacred currents mediating between supernatural and earthly realms.

References

Bargna, Ivo. African Art. New York: Prestel, 2000.

Fischer, Eberhard. Masks and Masquerade in Africa. Basel: Museum für Völkerkunde, 1963.

Fischer, Eberhard, and Hans Himmelheber. The Arts of the Dan in West Africa. Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 1984.

Vandenhoute, Paul. "Les Dan de la Côte d’Ivoire." Journal de la Société des Africanistes 18, no. 1 (1948): 5–88.

Dan Headdress

Ivory Coast

Early 20th Century

Fabric, Cowrie Shells, Beads, Fiber, Animal hair, Hide

Collection of Daniel Jones

Objects created to safeguard, ward off negative forces, or embody protective spirits.

Protection

These paired bochio (empowered object) figures originate from the Ewe peoples of Ghana and Togo, where they function as significant and powerful ritual instruments within the Ewe cosmology. Unlike objects made primarily for aesthetic appreciation, and much like the majority of traditional African art and material culture, these are activated works of power, created to engage spiritual forces and accomplish various tasks such safeguard the individual, family, or community. They are not just statues but living mediators of good, protective spirits, whose potency is enhanced through consecration, libations, and repeated offerings (Blier, 1995).

The figures are carved from wood and engulfed in layered cloth wrappings such as red, blue, brown, and earth-toned fabrics that bear traces of ritual handling and weathering, accumulating a patina over time. Red is especially significant in Ewe beliefs as a color associated with vitality, warfare, and the channeling of spiritual energy. The cloth layers and other additives accumulate over time by being added during ceremonies to increase the object's spiritual efficacy. Necklaces of cowrie shells and other organic materials further amplify their protective force, binding natural and supernatural power into the figure.

This bochio pair has rough surfaces and encrustations of sacrificial materials, which reflect their previously active ritual lives. Some objects such as these bochio would be "planted" in the ground or placed among other objects on an altar, thus creating the lack of uniformity in appearance of the object regarding its legs. In traditional Ewe practice, such accumulations of materials on an object are not damage, rather they are essential evidence of their spiritual labor and prowess. Each addition, whether fabric, libation, or organic substance, represents an ongoing dialogue between humans and divine forces.

These two figures, presented together, suggest a paired protective function, possibly safeguarding a household, couple, or family group. Bochio may be commissioned by individuals or families seeking resolution to misfortune, illness, or conflict, and they embody the community’s deep investment in spiritual balance, protection, and superstition (Greene, 1996). This bochio pair exemplifies the ways in which traditional African art cannot be separated from lived religious practice, where objects, people, and spirits are woven into a dynamic web of protection, healing, power, much like many religious systems, but more alive in daily lives within traditional African cultures.

References

Blier, S. P. (1995). African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power. University of Chicago Press.

Greene, S. E. (1996). Gender, Ethnicity, and Social Change on the Upper Slave Coast: A History of the Anlo-Ewe. Heinemann.

Ewe Bochio Couple

Togo

Early-Mid 20th Century

Wood, Fabric, Organic Substances, Cowrie Shells

Collection of Daniel Jones

Fon Bochio

Benin

Early-Mid 20th Century

Wood, Organic Substances, Oil

Collection of Daniel Jones

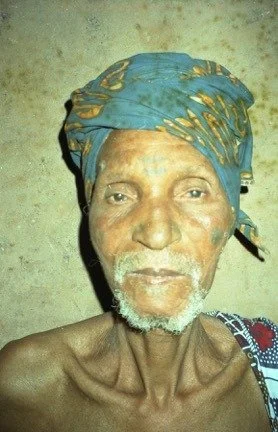

Collected In Situ by Luc and Ann Huysveld (Ann De Pauw). Photo examples of the Healer who made this object (Mr. Seifide) are below and were taken by Ann De Pauw during their time residing in Benin studying the culture. There are also a couple photos of other bochio Mr. Seifide made while they are in use, planted in the ground for reference. You can see stylistic similarities in the figures in these photos and the one in Sacred Currents.

Mr. Seifide

Planted Bochio

Planted Bochio

This three-headed figure is a bochio, a spiritually charged object central to the religious practices of the Ouatchi people of southern Benin, a subgroup within the larger Ewe cultural sphere. The term bochio (from bo, meaning “empower” or “empowered,” and chio, means “cadaver”) conveys the conception of these objects as material vessels imbued with spiritual vitality (Blier, 1995). Far from being inert sculptures, bochio are understood as active mediators in relationships between the human and spiritual realms.

This figure is carved in anthropomorphic form, with a prominent head and elongated body, though its surface is heavily encrusted with layers of sacrificial materials. Such accretions, including earth, oils, and other organic matter, were ritually applied to “feed” the figure and activate its force (Monroe, 2014). The binding elements visible around its torso and neck further attest to its function: the tying of cords and insertion of organic matter were ritual techniques designed to bind hostile forces, restrain malevolent spirits, or direct protective power toward the owner or community. An extremely interesting component of this bochio are the three heads (two in the front, one in the back), which is referred to as a janus head. The resulting rough and weathered appearance reflects both the material history of ritual use and the object’s transformation into a prominent object of spiritual potency.

This bochio exemplifies the entanglement of materiality, ritual practice, and belief in West African religious systems, demonstrating how sculpture could serve as both an embodiment of protective force and a record of sustained devotional engagement.

References

Blier, Suzanne Preston. African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power. University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Monroe, J. Cameron. “Vodun Arts in Urban Spaces: The Production of Social Memory in Abomey.” African Arts, vol. 47, no. 4, 2014, pp. 8–23.

Nooter, Mary H. Secrecy: African Art That Conceals and Reveals. Museum for African Art, 1993.

Ouatchi Bochio

Benin

Late 19th-Early 20th Century

Wood, Fiber, Cloth, Animal Bone, Chicken Feather, Organic Substances

Collection of Daniel Jones

Twin Figures in West African Art: Grief, Memory, and the Continuity of Life

Among the Ewe, Fon, Adja, and Yoruba peoples of West Africa, the birth of twins has long been understood as an extraordinary event and as a blessing. In West Africa, twin birth rates are very high, but, unfortunately, so are infant mortality rates and other forms of mortality. Across these cultures, when a twin passes away, artists and families create carved wooden figures known variously as venavi (Ewe), hohovi (Fon), togbovi (Adja), or ibeji (Yoruba). These figures act as material mediators between the living and the spiritual realm, transforming grief into an enduring cultural practice.

The birth of twins (and by extension, their loss) holds exceptional significance in West African cosmologies. Twins are believed to embody duality and balance, serving as manifestations of divine presence or supernatural intervention (Lawal, 1995). Their sudden death, therefore, disrupts this equilibrium, necessitating acts of ritual remembrance. The carved twin figure becomes both a spiritual surrogate for the deceased and a tangible focus of mourning.

In Yoruba belief systems, the ere ibeji (literally “sacred image of the twin”) functions as a living vessel for the spirit of the departed twin. The bereaved mother tends to the figure daily by washing, dressing, feeding, and adorning it with beads or even cowries, thereby maintaining the child’s presence in the family (Thompson, 1971). This practice is not seen as idolatry but as a form of relational continuity, ensuring that the twins’ spirit remains in harmony with the living community.

Among the Ewe, Fon, and Adja of Ghana, Togo, and Benin, similar traditions persist. The venavi, hohovi, and togbovi figures are typically carved in pairs or individually in the likeness of the deceased child. These sculptures embody a profound emotional realism—expressed in the serene, human-like features and polished surfaces that invite touch and care (Argyropoulos, 2016). They may be kept in domestic shrines or personal altars, serving as ongoing conduits for prayer, remembrance, and spiritual protection.

Under the exhibition’s theme of “Grief and Memorialization,” these twin figures reveal the deep intersection between art, mourning, and metaphysics in West African thought. They are not static memorials of loss but dynamic embodiments of the belief that death does not sever familial bonds. Instead, it transforms them. The ongoing care of the twin figure reflects a cosmology where the spiritual and material coexist—where the departed are never truly absent but continue to participate in the moral and emotional life of the community.

Each figure in this collection, whether from the Yoruba, Ewe, Fon, or Adja, bears the imprint of both personal sorrow and cultural resilience. Together, they testify to a universal human impulse: to give enduring form to grief and to find, through art, the means to reconcile loss with love.

References

Argyropoulos, D. (2016). Ewe Venavi Figures: Art, Twins, and the Living Dead in Southern Togo. African Arts, 49(4), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1162/AFAR_a_00272

Lawal, B. (1995). The Gelede Spectacle: Art, Gender, and Social Harmony in an African Culture. University of Washington Press.

Thompson, R. F. (1971). Yoruba Art and Aesthetics. The Art Bulletin, 53(4), 467–482.

This bochio power figure originates from the Fon peoples of Benin. Bochios are anthropomorphic figures created as conduits for spiritual force and have many functions, embodying the intersection of material form and metaphysical power. Unlike sculptures meant solely for aesthetic appreciation, bochios are functional ritual objects activated through the aid of diviners. The purpose of a bochio or power figure is typically utilized to safeguard individuals, families, or communities, grant wishes, and be a direct counter to malevolent forces, illness, or social discord (Blier, 1995).

This example demonstrates the layered complexity of bochio construction. The carved wooden core forms the human-like figure, but its spiritual potency derives from the accumulation of added substances such as iron fragments, clay, cowrie shells, and medicinal matter. Iron is associated with Ogun (the deity of war and iron), is frequently inserted into these figures to enhance their communicative, protective, and combative power. You can see the figure holding a staff known as an asen (iron altar or staff), which is a significant object among the Fon people to aid in communication with ancestors and spirits. Cowrie shells, long used in West Africa as currency and divinatory tools, symbolize both wealth and communication with the spiritual realm. The surface encrustations of earth and sacrificial materials further testify to the figure’s ritual use, embedding it within cycles of offering and invocation (Law, 1997).

The raised arm holding the asen suggests a combative posture, focusing on the figure’s role as a defender against harmful forces. Bochio are not static objects, they are active participants in spiritual practice: they are “charged” through libations, prayers, and ritual manipulations, creating a reciprocal bond between the human community and the spiritual energies embodied in the figure. As Suzanne Blier notes, these works are “living entities” whose efficacy is measured not by complete artistic refinement but by spiritual power and community reliance (Blier 1995, 56).

This bochio shows how African material culture and traditional arts exceed Western categorizations of “object” or “artifact.” Instead, it exemplifies a dynamic, interactive, sacred technology, rooted in materials yet extending into realms of healing, protection, and spiritual communication.

References

Blier, Suzanne Preston. African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Law, Robin. The Slave Coast of West Africa 1550–1750: The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on an African Society. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997.

Rush, Dana. “Vodun Arts in Urban Spaces: The Mami Wata Shrines of Contemporary Benin.” African Arts 33, no. 4 (2000): 60–75.

Fon Bochio

Benin

Early 20th Century

Wood, iron, cowrie shells, glass, clay, and other organic materials

Collection of Daniel Jones

Grief & Memorialization: Twin Figures of West Africa

Among the Ewe people of southeastern Ghana, Togo, and southern Benin, carved wooden figures known as venavi (twin figures) hold profound spiritual and social significance. Traditionally commissioned to represent deceased twins, venavi serve as memorials attached to grief, Ewe cosmology, and are living presences within the household. Venavi are not created as mere artistic objects but as vessels embodying the spiritual essence of the departed, ensuring that bonds between the living and the deceased remain unbroken (Ross, 2008).

The set of eight venavi presented within a large wooden home exemplifies the communal and spiritual aspects of venavi, and it is incredibly rare to see such an ensemble. The venavi grouping reflects the symbolic family unit. The wooden structure could have been used as a "daycare" house, and there is uniformity in each figure clothed in similarly patterned textiles and arranged together as a family or with a close relationship. Such an arrangement suggests the continuity of kinship or spiritual relationships beyond death, reinforcing the Ewe understanding of personhood as relational and extending to the spiritual and earthly realms (Gadzekpo, 2018).

Care of venavi is an active, ongoing practice. Families and those with close relationships feed, bathe, and dress the figures as they would living kin, and carry them with them throughout daily activities, affirming reciprocal obligations with spiritual, symbolic reasoning. The cloth wrappings here are significant, for they not only humanize the figures but also reflect the importance of textiles in Ewe cultural aesthetics and social identity (Picton, 1995). Venavi are also often carried by the mother or relatives using wrappings or garments to configure the venavi to the waist or core.

As a whole, this venavi ensemble speaks to the Ewe philosophy of life, death, and continuity, where the boundaries between the living and the departed are permeable and continuous. Rather than severing relationships, death reconstitutes them in new forms. These venavi, housed collectively, embody the enduring ties of kinship, memory, and ritual care that anchor Ewe spiritual and social life.

References

Gadzekpo, A. (2018). Cultural Expressions of the Ewe: Continuity and Transformation. Accra: Woeli Publishing Services.

Picton, J. (1995). Textiles of Africa. London: British Museum Press.

Ross, D. H. (2008). Art of West Africa. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ewe Venavi in a Large Home

Ghana

Mid 20th Century

Wood, Cloth, Pigment, Kaolin Clay, Organic Substances

Collection of Daniel Jones

The following Photos are taken by Jean-Claude Moschetti while in Benin documenting active twin figure usage. The photos show twin figures being held by a caring mother, being bathed, put to rest, and twin figures being cared for at a daycare, nursery-like place with a caregiver. These “nurseries” are established so twin figures can be cared for in case a family is unable to care for their twin for the time being. The photos of the care facility are profound because the set of eight twin figures discussed above is more than likely from a similar setting, making it rather rare. It is important to note that all twin figure communities can behave in unique fashions, and what is done within one region, country, or people group, may not be replicated across others. The following photos and practices are more related to the Fon (Hohovi) and Ewe (Venavi) groups. Practices such as nurseries for twins may not be found among other people groups such as the Yoruba (Ibeji).

Among the Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria, the carving of ere ibeji (twin figures) represents one of the most significant and renowned sculptural traditions in traditional African art. The Yoruba have one of the highest rates of twin births in the world (as do other people groups of West Africa), and twins (ibeji) are regarded as spiritually powerful beings. When one or both twins die in infancy or childhood, unfortunately, a frequent occurrence due to historically high mortality rates, the family commissions a sculptor to carve a wooden effigy to house the spirit of the deceased child. This effigy is not a memorial but rather a living vessel that ensures the continued presence and influence of the twin within the family and community (Drewal 1989; Lawal 1996).

The figure shown here, carved from hardwood and adorned with beads around the neck and waist, exemplifies the aesthetic conventions of Yoruba ibeji sculpture. The elongated body, prominent head, and symmetrical posture emphasize the Yoruba conception of the head (ori) as the seat of destiny and spiritual power (Abiodun 1994). Incised facial scarification reflects cultural ideals of beauty, lineage identity, and social belonging. The beads, which may have once included cowrie shells or additional ornamentation, serve not only as adornments but also as protective devices, mediating the figure’s spiritual efficacy.

Families cared for ibeji figures as if they were living children: feeding them, washing them, dressing them in cloth, and rubbing them with oils. In return, the ibeji spirit was believed to provide blessings of fertility, health, and prosperity, while neglect could bring misfortune (Thompson 1971). Thus, these figures are not inert objects but active participants in Yoruba religious life, embodying a complex interplay between art, spirituality, and kinship.

Today, ibeji figures remain important testaments to Yoruba philosophy and artistry. They reveal how communities navigated and continue to navigate life, death, and continuity through the mediation of sculpture, affirming the Yoruba conviction that spiritual and material realms are inextricably bound.

References

Abiodun, Rowland. African Aesthetics: The Yoruba Example. African Arts, Vol. 27, No. 4, 1994.

Drewal, Henry John. Yoruba Ritual: Performers, Play, Agency. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989.

Lawal, Babatunde. “À Yà Gbó, À Yà Tó: New Perspectives on Edan Ògbóni.” African Arts 29, no. 1 (1996): 40–53.

Thompson, Robert Farris. African Art in Motion: Icon and Act in the Collection of Katherine Coryton White. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1971.

Yoruba Ibeji

Nigeria

Early 20th Century

Wood, Beads, Iron, Fiber

Ewe Venavi, Togo, Mid 20th Century

Ewe Venavi, Ghana, Mid 20th Century

Fon Hohovi, Benin, Early 20th Century

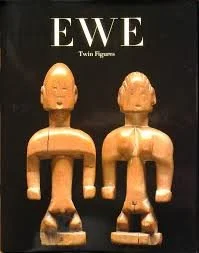

Ewe Venavi, Togo, Early 20th Century Published in Twin Figures by Henricus Simonis

Haitian Drapo Vodou: Sacred Currents in the African Diaspora

Haitian drapo Vodou (Vodou flags) are among the most spiritually charged and visually intricate art forms within the African diasporic tradition. These sequined and beaded banners are created and used in Vodou temples (hounfors) to honor the lwa (spirits) during rituals, ceremonies, and processions. Each drapo serves as both a devotional offering and a spiritual conduit, channeling divine presence through its intricate craftsmanship and symbolism (Cosentino, 1998). Artists such as Antoine Oleyant, Clotaire Bazile, and Sylva Joseph have been pivotal in transforming the drapo Vodou from purely ritualistic objects into highly regarded works of contemporary sacred art. Oleyant, for example, is known for expanding the narrative and figural possibilities of the drapo, incorporating expressive imagery that reinterprets the pantheon of lwa (Averill, 1997). Similarly, Bazile and Joseph’s works merge traditional iconography with artistic innovation, maintaining deep reverence for ancestral spirituality while asserting creative individuality. Haitian drapo are renowned, revered, and collected because of their aesthetic beauty and deep significance and symbolism. Each drapo (depending on the size) can include thousands of glass beads and sequins, and they are all hand done exemplifying artistry and skill. In Sacred Currents: Spirituality in African Art, there are two Antoine Oleyant drapo, two Clotaire Bazile drapo, and two Sylva Joseph drapo, granting a phenomenal opportunity to observe quality examples of Haitian drapo.

The aesthetic and spiritual power of drapo Vodou cannot be separated from the historical experience of the transatlantic slave trade. Enslaved Africans from West and Central Africa, particularly from the Fon, Ewe, Adja, Yoruba, and Kongo cultural spheres, brought with them complex religious systems that emphasized communion with spiritual forces and reverence for ancestors (Thompson, 1983). Under colonial oppression in Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), these traditions merged with imposed Catholicism, forming a unique system of religious syncretism that allowed African beliefs to survive in disguised form (McCarthy Brown, 1991). For instance, the warrior lwa Ogou was syncretized with St. Jacques Majeur (St. James the Great), a Catholic saint often depicted on horseback bearing a sword. In the drapo, this imagery symbolizes not only divine strength and protection but also resistance, freedom, and the indomitable spirit of African identity under bondage (Richman, 2008).

Including Haitian drapo Vodou in the exhibition Sacred Currents: Spirituality in African Art underscores the enduring continuity of African spiritual philosophies across the Atlantic world. These flags stand as visual affirmations of faith, transformation, and resilience—bridging Africa’s sacred traditions with their diasporic evolution in the Caribbean. As Thompson (1983) notes, African religious systems thrive through creative adaptation rather than static preservation, and the drapo Vodou embodies that living continuum. Displayed alongside Yoruba ashe objects or Fon bochio figures, these works reveal a shared cosmological vision in which the spiritual and material worlds are profoundly interconnected. In this sense, Haitian drapo not only honor the lwa but also represent a living testament to Africa’s unbroken spiritual legacy—a sacred current flowing through art, history, and faith.

References

Averill, G. (1997). A day for the hunter, a day for the prey: Popular music and power in Haiti. University of Chicago Press.

Cosentino, D. (Ed.). (1998). Sacred arts of Haitian Vodou. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

McCarthy Brown, K. (1991). Mama Lola: A Vodou priestess in Brooklyn. University of California Press.

Richman, K. (2008). Migration and Vodou. University Press of Florida.

Thompson, R. F. (1983). Flash of the spirit: African and Afro-American art and philosophy. Vintage Books.

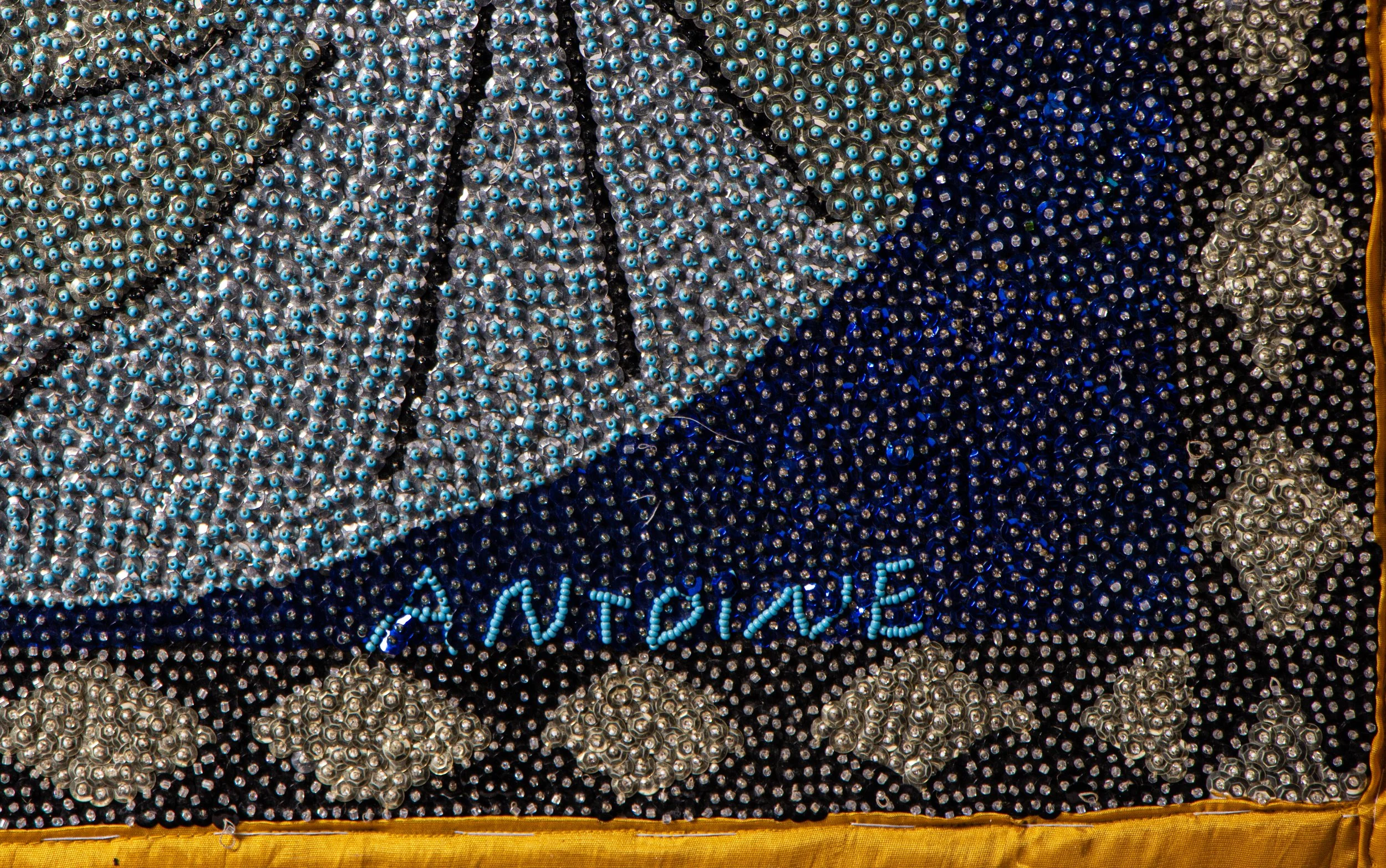

This beaded drapo Vodou by Antoine Oleyant (1955–1992) depicts La Sirène, one of the most powerful and enigmatic spirits (loa or lwa) in Haitian Vodou. Rendered with luminous glass beads and sequins that evoke the movement and reflection of water, Oleyant’s flag demonstrates his mastery of the form—uniting sacred devotion, visual rhythm, and modernist composition. The artwork’s shimmering surface and stylized imagery embody both the beauty and depth of La Sirène’s dominion beneath the sea, as well as her complex role in the history and spiritual consciousness of the African diaspora.

La Sirène and Religious Syncretism

In Haitian Vodou cosmology, La Sirène is the lwa of the sea, associated with beauty, wealth, music, and spiritual depth. She is often paired with Agwe, the maritime spirit who governs the ocean, symbolizing the feminine and masculine principles of the aquatic realm (Cosentino, 1998). As a mermaid-like figure, La Sirène embodies both allure and mystery, drawing connections between the physical and spiritual worlds. Her mirror—a common motif in her depictions—represents self-reflection and the power of seeing beyond the material into the divine (McCarthy Brown, 2001).

Through the process of religious syncretism, La Sirène is often linked to Our Lady of Regla or the Virgin Mary, reflecting the historical blending of African spiritual traditions with Catholic iconography during the colonial period. This fusion allowed enslaved Africans to maintain and disguise their spiritual practices under the guise of Christian worship. Thus, La Sirène becomes a symbol of resistance and resilience—a sacred figure of both survival and transformation (Hebblethwaite, 2012). Beyond La Sirene’s associations with beauty, allure, and fortune, La Sirène’s power carries profound historical resonance, deeply rooted in the trauma and survival of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

La Sirène and the Memory of the Middle Passage

The Atlantic Ocean is both the geographical and spiritual site of the Middle Passage, the forced crossing that transported millions of Africans into enslavement in the Americas. Within this historical context, La Sirène represents more than a sea spirit; she embodies the collective memory of the crossing and the souls lost to the depths (Hebblethwaite, 2012). Haitian oral traditions and Vodou cosmology regard the ocean as a liminal space between life and death, freedom and captivity, home and exile. The sea, ruled by La Sirène and Agwe, became both the grave and the gateway for ancestral spirits. In this way, La Sirene is a guiding, protecting, nurturing, loving, and caring spirit for those who tragically passed away for various reasons during the transatlantic voyage.

Oleyant’s Artistic Mastery

Antoine Oleyant revolutionized the art of drapo-making. Before his time, flags were primarily functional ritual objects used in Vodou ceremonies to honor spirits and mark sacred spaces. Oleyant elevated the medium through innovative designs, complex compositions, and narrative storytelling that extended beyond liturgical function. His flags, such as this portrayal of La Sirène, employ dynamic compositions, stylized forms, and modernist abstraction to convey the ethereal power of the lwa (Ross, 1995).

This particular drapo is monumental not merely for its scale, but for its conceptual depth and craftsmanship. Oleyant integrates sequins in gradients that create depth and texture, evoking the shimmering quality of water that surrounds La Sirène. The figure’s mask-like face, a signature of Oleyant’s style, situates the work between the sacred and the symbolic, merging African aesthetics with Haitian spirituality. The bold colors and geometric structure convey movement, echoing the undulating rhythms of the sea and the music associated with the lwa’s ceremonies.

Oleyant’s contributions to Haitian art were cut short by his early death in 1992, yet his influence endures. His flags bridge the realms of devotion and contemporary art, embodying the resilience of Haitian spirituality and its capacity for renewal. Today, his works reside in major museum collections, including the Fowler Museum at UCLA and the Smithsonian Institution, where they continue to redefine global perceptions of Vodou as a sophisticated, living spiritual and artistic tradition.

References

Cosentino, D. (1998). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

Hebblethwaite, B. (2012). Vodou Songs in Haitian Creole and English: Bilingual Anthology and Translation. Temple University Press.

McCarthy Brown, K. (2001). Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn (Updated ed.). University of California Press.

Ross, M. (1995). Art That Heals: The Image as Medicine in Haiti. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

Haitian Drapo (La Sirene)

Antoine Oleyant

Haiti

1980s

Fabric, Sequins, Beads

Collection of Daniel Jones

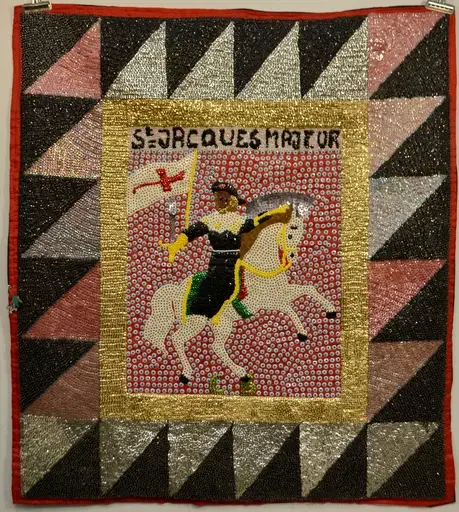

Haitian Drapo (St. Jacues Majeur)

Clotaire Bazile

Haiti

1980s

Fabric, Sequins, Beads

Collection of Daniel Jones

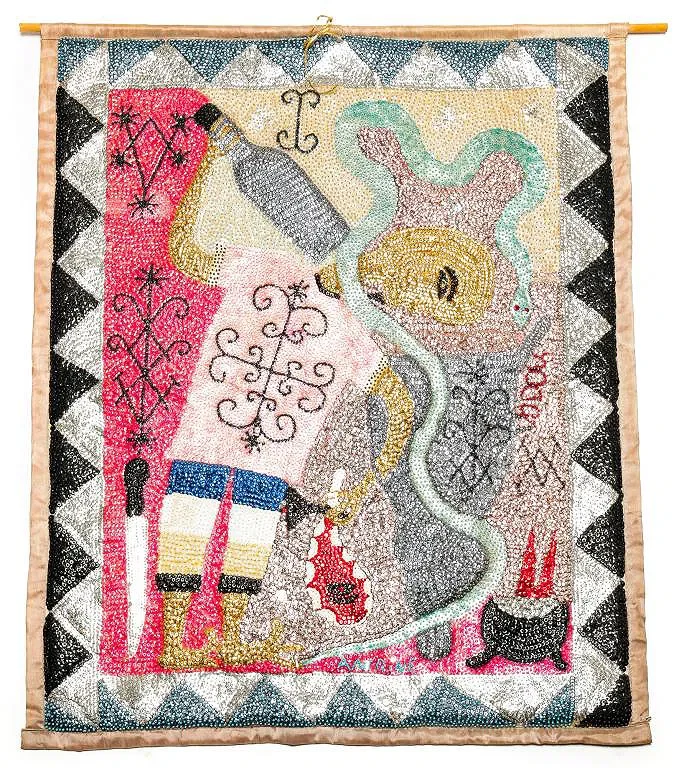

This drapo Vodou (Vodou flag) by master artist Clotaire Bazile depicts St. Jacques Majeur (St. James the Greater), one of the most venerated figures in both Roman Catholic and Haitian Vodou iconography. The flag exemplifies Bazile’s mastery of beadwork and sequined embroidery, combining spiritual symbolism, syncretism, and exceptional craftsmanship characteristic of his oeuvre. The flag’s geometric border of alternating silver, black, and pink triangles frames a central figure rendered in dense sequin fields, where St. Jacques—mounted on a white horse and bearing a sword and banner—is both a Catholic saint and a powerful lwa (spirit) in the Vodou pantheon.

In Haitian Vodou, St. Jacques is commonly identified with Ogou Feray, one of the warrior spirits of the Rada and Petro nations. Ogou represents strength, justice, leadership, and the revolutionary power that led enslaved Africans to resist colonial domination. The saint’s depiction on horseback holding a sword evokes both Christian chivalric imagery and the martial symbolism of Ogou, who wields iron weapons and governs war, protection, and political authority (Cosentino, 1995). This duality underscores Vodou’s religious syncretism, where African deities were concealed beneath Catholic saintly forms during the colonial period, a strategy that preserved ancestral worship under the guise of Christianity (Desmangles, 1992).

Bazile’s technical approach situates him among the most renowned drapo artists of the late twentieth century. Emerging from the lineage of artists from the Port-au-Prince neighborhood of Bel-Air and the Vodou temple ateliers established in the mid-1900s, Bazile’s work demonstrates meticulous symmetry, layered textures, and vibrant chromatic harmony (Brodsky, 2008). His beadwork transcends mere ornamentation; each sequin and stitch functions as an act of devotion and invocation, transforming the flag into a sacred conduit for spiritual presence during Vodou ceremonies.

The figure of St. Jacques Majeur/Ogou also carries deep historical resonance. During the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), Ogou became an emblem of courage and resistance—embodying the military spirit that inspired enslaved Africans to fight for freedom (Ramsey, 2011). The saint’s white horse, radiant armor, and red cross reference not only Catholic martyrdom but also the triumph of freedom over oppression, themes central to Haiti’s national and spiritual identity.

This drapo exemplifies Bazile’s status as a master flagmaker, merging sacred imagery, national history, and personal artistry into a unified visual theology. His works are not merely liturgical textiles but also vibrant historical documents—articulating Haiti’s enduring dialogue between African cosmology and Western iconography.

References

Brodsky, M. (2008). Vodou Flags. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

Cosentino, D. (1995). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

Desmangles, L. G. (1992). The Faces of the Gods: Vodou and Roman Catholicism in Haiti. University of North Carolina Press.

Ramsey, K. (2011). The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti. University of Chicago Press.

Haitian Drapo (Damballah)

Antoine Oleyant

Haiti

1980s

Fabric, Sequins, Beads

Collection of Daniel Jones

In this work, the lwa or loa depicted is Dambala, who is often depicted as a serpent. In this drapo, Dambala is rendered with a flowing, curvilinear body that winds across the flag, symbolizing fertility, divine continuity, and the cyclical essence of life. In Vodou cosmology, Dambala Wedo and his consort, Ayida Wedo, represent the male and female principles that sustain creation, mirroring the rainbow and serpent as sacred forces uniting heaven and earth (Desmangles, 1992). The snake’s form is intertwined with veves, the ritual symbols drawn during ceremonies to invite the lwa’s presence. The inclusion of ritual tools such as the machete, bottle, and altar flames reinforces the drapo’s sacred function as a spiritual invitation, rather than a mere decorative textile.

Oleyant’s composition merges sacred geometry and abstraction with meticulous beadwork, a hallmark of his artistry. He was among the first artists to integrate painterly techniques and asymmetrical composition into drapo Vodou, modernizing the tradition while retaining its ritual authenticity (Brodsky, 2008). His workshop practice in Croix-des-Bouquets established him as both a master craftsman and a cultural innovator, inspiring a generation of artists including Clotaire Bazile and Sylva Joseph. Oleyant’s innovations helped elevate drapo from temple altars to international art galleries, transforming perceptions of Vodou art as deeply spiritual yet visually avant-garde (Ramsey, 2011).

Dambala’s presence in Vodou is deeply rooted in African cosmology, particularly linked to the Dahomean deity Dan, the primordial serpent of the Fon and Ewe peoples of West Africa (Thompson, 1983). This continuity illustrates how Vodou retains ancestral memory across the Atlantic, fusing African theology with Catholic iconography and Haitian experience. The shimmering sequins and reflective materials evoke light and movement—metaphors for Dambala’s purity and transcendence. In Vodou ceremonies, flags like this are carried and waved to signal the arrival of the lwa, transforming dance, sound, and color into a multi-sensory act of worship.

References

Brodsky, M. (2008). Vodou Flags. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

Cosentino, D. (1995). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

Desmangles, L. G. (1992). The Faces of the Gods: Vodou and Roman Catholicism in Haiti. University of North Carolina Press.

Ramsey, K. (2011). The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti. University of Chicago Press.

Thompson, R. F. (1983). Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. Random House.

Opening Reception: October 17, 2025

The following photos from the Sacred Currents: Spirituality in African Art Reception were taken by Robert Connors from the Lake Wales News.

Schedule a Docent-Led Tour

Elevate your experience of "Sacred Currents" with a free, docent-led tour. Our knowledgeable guides will lead you on a deeper exploration of the exhibition, providing context and insight that brings each artifact to life. Tours can be tailored to suit the interests of your group, whether you're a curious elementary school class, a college-level art history course, or a private group of enthusiasts. Discover the hidden stories and spiritual significance behind the artwork in a personal, engaging way.

Teacher & Student Resources

Enhance your students' learning experience with our classroom-ready activity guide for the "Sacred Currents" exhibition. This free PDF offers a range of engaging activities and discussion questions that align with K-12 curriculum standards. The content focuses on key themes like symbolism, cultural history, and the vital role of art in society, providing educators with a valuable tool to deepen student engagement and understanding before or after their visit.